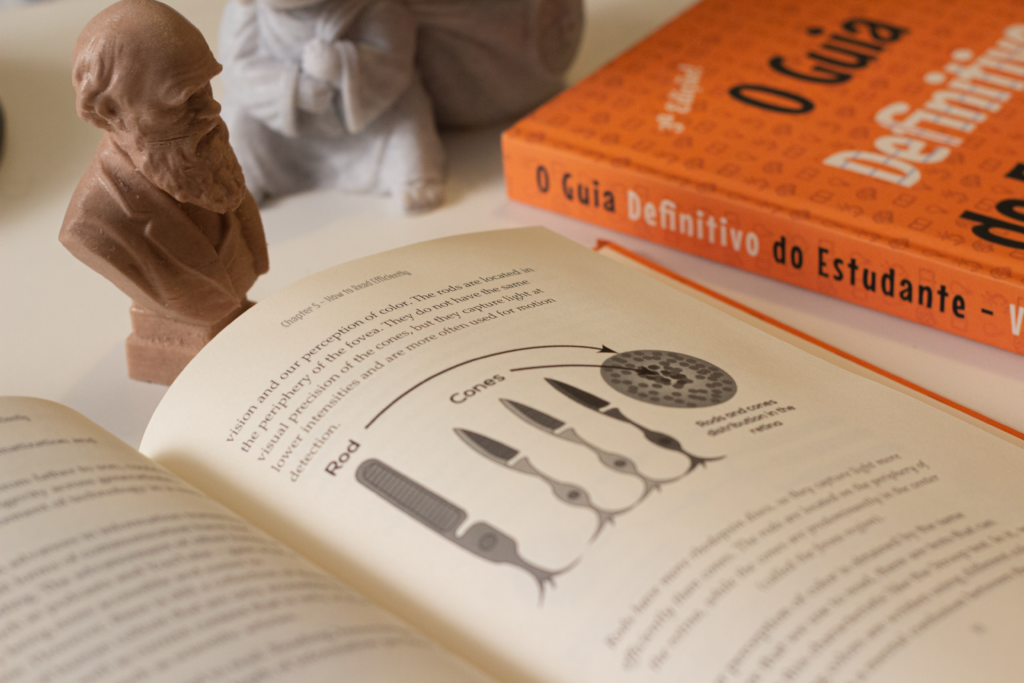

My book on learning – The Student’s Definitive Guide

The third edition of my book is out! It covers topics of neuroeducation – how to learn better and how to retain what you have learned.

The topics I cover describe the techniques I used to graduate cum laude in prestigious Masters degree study in Neuroscience Research and how I approach acquiring new skills, including language learning, programming and music.

I have written, edited, illustrated, translated and published the book myself. Along the way I needed to learn many new skills, which are a meta-showcase of what I talk in the book itself.

Kindle version in English available on Amazon

Versão e-book em Português na Amazon brasileira

If you choose to buy it, I sincerely appreciate the support! I hope the book is useful.

THE FOLLOWING TEXT IS A SNEAK PREVIEW OF THE BOOK’S PREFACE.

Preface

During elementary and high school, I had always been a student who got really high grades. I wasn’t necessarily a good student, per se, but I paid attention in class and that made me do well on the exams.

A nagging realization I had the day after graduating from high school was “I don’t remember almost anything from school. At all.” I had spent a good part of my, until then, seventeen years of life in an institution whose purpose was to teach me, but if I had to put on paper “What percentage of things do I remember from elementary, middle and high school”, my answer would be less than one percent.

While I was in elementary school, my “good memory” was obviously a benefit – it meant I didn’t have to struggle to get good grades. Unfortunately, this meant that I never developed good study habits, which made my transition to higher education very turbulent.

After completing high school, I started my Bachelor’s Degree in Biological Sciences at one of the top institutions in Brazil. I immediately went from being one of the top students in the class, like I was in high school, to being someone with mediocre grades.

For a few semesters, I applied the same ‘study technique’ I used to use in high school: go to class, study from the teacher’s slides, review a few days before the exam.

Clearly that wasn’t working: the volume and density of information that I needed to learn in university is significantly greater than in high school. I felt stressed throughout the semester, and when I stopped to sit and study, I didn’t know how to prioritize the material.

For a long time, I just couldn’t understand what I was doing wrong. I blamed teachers for having unrealistic expectations of students; I blamed my schedule, which didn’t leave enough time for me to study; I blamed myself, thinking I wasn’t smart enough to do that bachelor.

What made me not abandon the course, at the time, was a unique opportunity: having the chance to be paid by the Brazilian government to study for a year at the University of Melbourne, one of the best universities in the world.

The scholarship I received would be from the Science without Borders program – which, at the time, was sending Brazilian students to other countries with little expectation of return for the population, which brought much criticism about excessive public spending.

While the program’s lack of academic rigor benefited me – literally anyone with an average academic score could participate – I always had it in my mind that I would prove everyone wrong about the quality of this program. I wanted to prove that there were, yes, excellent students being sent out. I was determined that I could be an example to other students—by putting in the effort, getting excellent grades, doing excellent research in my internship, and applying that knowledge when I got back to Brazil, one year later.

Said and done: I started studying even before classes started. After classes started, I was probably the student who spent the most hours studying for every subject I took.

I studied a lot. I woke up at 6 am, went to classes in the morning, tutoring sessions and workshops in the afternoon and often stayed in the library until 9 pm. On weekends I spent entire days at the library.

My mental and physical health were very compromised: I had serious anxiety and depression problems during this period and I gained about 50 lbs. In my mind, this was all temporary and all my efforts would pay off at the end of the semester.

“What was the result of this semester?” – you must be asking yourself.

Mediocre grades. I almost failed two subjects – 53% and 56% was my final grade in those – and got less than 70% in the other two that I passed more comfortably.

One detail that made this experience more shocking is that, according to the government’s program guidelines, if you failed two subjects, you had to return to Brazil and give all the scholarship money back (approximately 80 thousand reais at the time). That would mean that I would have put me and my family in a risky financial situation, possibly for years.

It was in this moment of existential shock that I finally realized that I was doing something wrong: I saw other students who took more difficult subjects than I did; they worked part-time, they had time for friends and family, and still got near-perfect grades.

What were they doing differently?

In this context of extreme frustration, I found a course called ‘Learning how to Learn’ taught by engineer Barbara Oakley on the Coursera platform.

I don’t like the phrase ‘It changed my life’ because it usually sounds like a cliché or exaggeration, but in this case, I can say that this course did indeed change my life.

The course’s premise is to break learning down into its simplest components and how to maximize the efficiency of your study hours, a subject that has fascinated me ever since.

Since I completed this course in January 2015, I have continued to study the subject of neuroeducation and productivity, trying to apply what I learned to my routine. In the following semester, I returned to Brazil and I took nine courses: I got seven maximum grades (above 90%) and two medium-high grades (80%). Since my return from Australia, I’ve managed to complete my degree taking 36 subjects, getting 27 top grades and 9 mid-upper grades.

But grades are only part of what I applied – I also studied more efficiently. As a result, I felt less stressed during semesters (I knew what I had to do and got my work done a lot faster than before), and I had more time to devote to other projects – I did a series of interviews with professors at my university, I managed to do internships almost every semester in conjunction with my subjects and I kept a blog, which after a few years culminated in the writing of this book.

Since the first edition of this book, I have taught the content described here in lectures and courses at various schools and universities, and the content covered appears to be universally applicable. The same techniques I used to graduate cum laude from a Masters in Neuroscience also can be used by a teenager in high school to get an A+ in a biology exam.

And that’s exactly why I fell in love with this topic of neuroeducation and how to learn better.

Why is this book relevant?

Currently, we live in the so-called knowledge age: more and more, manual processes are automated by machines or algorithms. The job market values people who are able to learn a lot of information quickly.

The ability to learn and master complex subjects, in a fast and efficient manner, is more valued today than ever before in history – and this ability, like any other skill, can be cultivated and developed.

There are efficient and inefficient ways of learning and retaining knowledge – unfortunately this is a topic that is rarely addressed during our school years. In school, the content is ‘given’ by the teachers and almost nothing is discussed about how they could study it in the best way possible.

At the same time, there is a current belief in the zeitgeist that people believe in innate abilities, both positively and negatively: Gary plays the guitar well because he was born with a gift. Maria will never be good at math; she just wasn’t born for that.

If you believe that people have fixed abilities, you probably believe this book is relatively useless.

However, my perspective is that human beings were born knowing anything – apart from some primordial instincts and reflexes inherent to the nervous system. We simply have the ability to develop abilities. There are no innate gifts or abilities, there is effort and practice to master something.

This doesn’t mean that anyone can learn anything, however, every person has the ability to learn magnificent things – even if they struggled to learn them at first.

That’s why I wrote this book, to try to help people who are not easy to learn to discover their potential. If you are not ‘a good student’, if you have difficulty learning new things, or if you have never developed your own study methods, the strategies described in this book will certainly help you.

I hope that the next few pages may be of some value to you.